Yada, Yamamoto, and the Art of Learning From Within

Yoshinobu Yamamoto doesn’t look like the conventional face of a modern power pitcher. He’s not 6’4”. He doesn’t tower over the mound. He’s listed at 5’10”, barely 176 pounds. Yet he throws 97–99 mph with ease, with command, with posture, with repeatability, and with one of the most efficient kinetic signatures of any pitcher in the world. To understand how that’s possible, you can’t start in the weight room. You have to start with how he learned to feel his body.

Before his MVP seasons, before the strikeout titles, before the big contract, Yamamoto crossed paths with a mentor named Yada — a trainer in Japan known not for traditional strength training, but for something most athletes never learn: how to explore movement from the inside out. Yada was a believer in mobility, rhythm, elastic loading, breath, balance, and something modern training culture often overlooks — the intelligence already built into the human body. He didn’t tell Yamamoto how to pitch. He taught him how to feel.

This was the turning point. Not programming. Not max strength. Not analytics. The turning inward.

The Foundation: The Five B’s

Yada’s training system can be summarized through five simple tools, each starting with a “B.” But they’re more than tools — they’re portals into how the body organizes itself in motion.

Breath

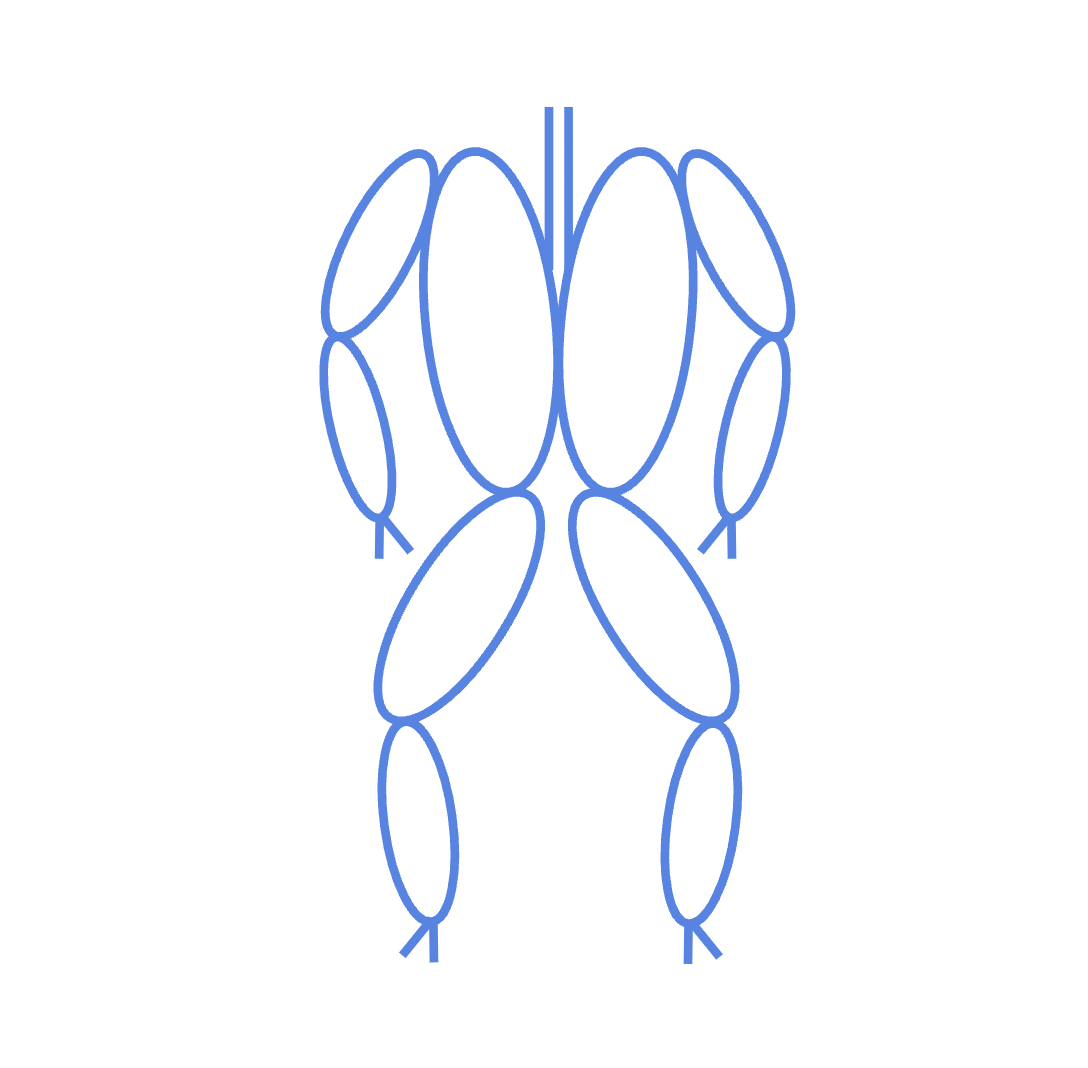

Breath is the regulator of rhythm, tension, and postural tone. When the diaphragm moves well, the ribs can rotate. When the ribs rotate, the spine can spiral. When the spine spirals, the pelvis can orient. When the pelvis orients, the hips can load. Breath isn’t something added to mechanics — it’s the source code of mechanics.

Most athletes breathe like they live in fight-or-flight, chest rising, ribs locked, pelvis stuck. Yamamoto learned to breathe low, into the bowl of the pelvis, expanding in 360°, softening the rib cage so that rotation was accessible without muscular strain. This is why he looks effortless — the system is pressurized, not braced.

Board

The board is a simple balance tool. It trains the tripod of the foot — big toe, fifth metatarsal, heel. When the tripod is stable, the knee aligns, the hip can rotate, and the spine can stack. When the foot is unstable, the entire kinetic chain collapses upward. Most pitchers leak power through the ground. Yamamoto learned to receive force from the ground.

On the board, he felt subtle weight shifts — forward/back, lateral, diagonal — learning how to control his center of mass with micrometer precision. This is how he maintains posture during a 70+% stride: the foot knows where it is.

Bar

The bar is not for lifting — it’s for rib cage mobility. Holding a bar overhead or behind the shoulders gives feedback on spinal rotation, rib flare, scapular glide, and trunk shape. Instead of “strengthening” the core by bracing, the bar teaches the ribs to move in a figure-8 pattern around the spine. This creates rotational elasticity rather than stiffness.

Pitch velocity is not about muscle — it’s about elastic recoil.

Bowl

The bowl refers to the center of mass — the pelvis — and how it sits, tilts, and rotates over the legs. Yada constantly emphasized finding the bowl and keeping it balanced. Most athletes leak rotation by tilting or dumping the pelvis. Yamamoto learned to coil and uncoil it like a spring, synchronizing pelvis rotation with rib rotation, which is the essence of the throwing spiral.

This is why his torso unwind looks smooth, not explosive — it’s happening in sequence, not all at once.

Bridge

The bridge represents spinal extension — not lumbar compression, but long-axis elastic length. When the spine is long, it can rotate. When it is short and compressed, rotation dies. Yamamoto trains bridging movements to maintain space between vertebrae, allowing the trunk to rotate around length, not force.

This is the key difference between violent throwers and elastic throwers.

Why This Matters for Velocity

Most 5’10” pitchers don’t come close to 98 mph. The conventional model says you need:

Long levers

Heavy weight training

Long stride created by hip mobility or strength

But Yamamoto’s stride length isn’t just long — it’s proportionally elite: over 70% of his height. That’s not flexibility for flexibility’s sake. That is full-body integration. The stride is not forced — the stride is accessed.

This is how a smaller frame generates enormous whip: full-body torsion, not muscular push.

The Javelin and the Mini Soccer Ball

Two of Yamamoto’s most iconic training tools are the javelin and the small soccer ball — both borrowed from Yada’s library of elastic and rhythmic movement.

The javelin lengthens the line from the fingers through the ribs into the pelvis. It exaggerates the throwing arc, forcing the athlete to feel sequencing rather than force. It teaches the arm to be a passenger, not the driver.

The mini soccer ball does the opposite — it reduces the radius of the movement. When an object is too small, the body must learn to create shape and space internally. It forces:

Forearm rotation

Shoulder centration

Scapular glide

This is how Yamamoto learned touch, spin, and feel. Not through cues. Through sensation.

Learning From Within

Yada didn’t try to “fix” Yamamoto. He didn’t say “do it like this.” He taught him to search. To explore. To listen. To notice. Their training was not about copying someone’s mechanics. It was about discovering what his body wanted to do when it was allowed to move naturally.

When Yamamoto takes those long pauses — sometimes 10, 20, even 30 seconds — just standing there, shifting his weight, rolling through his foot tripod, feeling the rib cage settle and the pelvis coil, that is the essence of learning from within. He’s not rehearsing a mechanical cue. He’s not running a checklist. He’s letting his body tell him where the next piece of tension lives, where there’s space to open, where there’s slack to gather before the throw. Most athletes skip this part entirely — they rush to the rep, to the output, to the visible action. But the real work is happening in the silent searching. That’s KQ. The ability to perceive your own internal landscape — to feel the subtle spirals, the weight shifts, the breath-driven rotations — and to reorganize yourself from the inside out. This is where movement intelligence is built. Not in the throw itself, but in the moments between.

This is why Yamamoto’s motion looks uniquely his. Not textbook. Not engineered. Not reverse-engineered from high-speed video. It is the natural expression of a body with:

A free rib cage

A spiraling spine

A centered pelvis

Stable feet

Responsive breath

This is movement that is felt, not imposed.

Conclusion

The modern sports world is obsessed with data, load, and force outputs. And yet, here is a 5’10” pitcher hitting 98 mph because he learned something most athletes never do: how to feel his body as a continuous, integrated chain.

The lesson is not that everyone should train with javelins or soccer balls or balance boards.

The lesson is that the body already knows how to move.

The work is learning to listen.

When you learn to feel, you stop forcing. When you stop forcing, you start flowing. And when you start flowing, power stops being something you create — it becomes something you access.

That’s the difference.

That’s Yamamoto.

That’s Yada.